Even today, even in the era of mainstream geekdom and publicly embracing guilty pleasures, I still cannot recommend two formative pieces of genre work from my childhood (the mid-’90s to early ’00s) without caveats. One was the first book series that I committed to with unabashed zeal, buying new installments monthly and absorbing myself in its world (nay, universe) for half a decade. The other was the TV series that first brought me online reading and then writing fanfiction; it was also my first lesson in the exhilaration-followed-by-disappointment of seeing a beloved series come back from cancellation not-quite-right. Animorphs and ReBoot shaped me as a fan and a writer; they were the first places where I learned how to make your characters grow with their audience, and how to depict war and its indelible consequences.

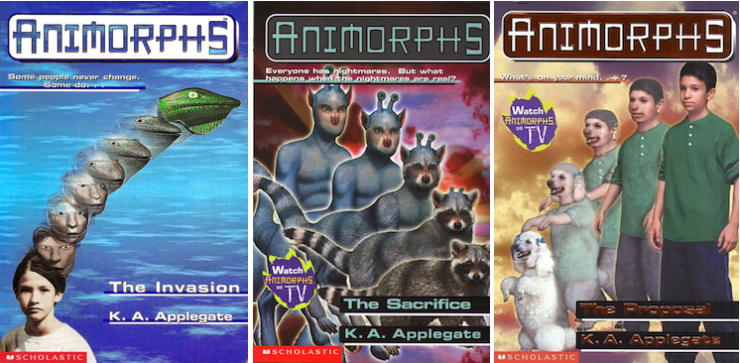

They are also cheesy as all get-out, with their ’90s-tastic Photoshop morphing book covers and CGI characters rapid-fire riffing on pop culture. But it was this unapologetically cartoonish packaging that made both series brilliant Trojan horses of a sort, ferrying impressively dark tales of trauma and recovery they might not have otherwise gotten away with.

Animorphs: Puberty Has Nothing on Morphing

“My name is Jake,” the leader of the Animorphs opens #1 The Invasion, first published in 1996. “That’s my first name, obviously. I can’t tell you my last name. It would be too dangerous. The Controllers are everywhere. Everywhere. And if they knew my full name, they could find me and my friends, and then… well, let’s just say I don’t want them to find me.”

In each subsequent book, whichever Animorph is narrating reiterates the same script, with the above introduction followed by some variation on this boilerplate text:

We can’t tell you who we are. Or where we live. It’s too risky, and we’ve got to be careful. Really careful. So we don’t trust anyone. Because if they find us… well, we just won’t let them find us. The thing you should know is that everyone is in really big trouble. Even you.

“They” are the Yeerks, alien slugs who worm their way into hosts’ brains—the victims then renamed Controllers—and seamlessly usurp their lives. As Jake and his friends soon learn, the Controllers could be anyone from their principal to Jake’s brother to a public figure promoting “The Sharing”—a community organization that, in between the barbecues and peer counseling, is a front for the Yeerks to learn about human society and recruit new members. And that “big trouble”? Is the Yeerks infiltrating Earth one body at a time while the planet’s only hope, the distant noble race of Andalites, do fuck-all to help.

The Animorphs’ opening monologue is hyper-dramatic, the equivalent of a child waving you close with urgent whispers that they have a secret, except they can’t actually tell you the secret. And the fact that it repeats in every single book (remember, these were published monthly) causes the reader to gloss over its warning, despite the actual seriousness of the increasingly messed-up adventures and battles in the ongoing war: Storming Yeerk pools every other week. Traveling to Area 51, to Atlantis, to a whole other planet. Hopping through time to wipe out an entire race during the era of the dinosaurs, or to debate whether or not to kill a non-Nazi Hitler in alternate-universe World War II. Imprisoning sociopathic “sixth Animorph” David as a rat, or negotiating with pacifist Yeerks who want the power to morph so they can escape the war. All while juggling their cover stories as typical teens who are totally not the only thing standing between the Yeerks and world domination.

Even as a kid, I knew the intro was eyeroll-inducing… but as an adult, I attempted to reconsider it from the Animorphs’ perspective: Imagine the all-consuming paranoia upon discovering that any stranger or loved one you encounter could be controlled by an extraterrestrial. You are a teenager; you’re already mistrusting authority figures, and then you find out that your parents, teachers, coaches, etc. can no longer be relied upon as confidantes, as protectors. Of course you’re going to be hyper-vigilant about protecting any hint as to your identity, because the alternative is at best slavery and at worst the end of all humankind as we know it.

This belated realization of the greater depth to the Animorphs series reflects the same sentiment I’ve seen echoed in a half dozen different pieces discovered in my research: Wait a minute, no one told me the Animorphs books were fucked UP. And yet, it’s right there on the cover—sort of. See, people liked to laugh at the super-cheesy, cartoonish morphing illustrations while never actually cracking open one of the books. That design has even become its own meme (and brought me this Pitbull morph, one of my favorite things on the Internet). But the reality of morphing, for our heroes, could not be further from these cartoonish covers. Like when Cassie becomes so traumatized by the termite’s hive mind that she attempts to demorph inside a log. Or when Rachel-as-grizzly-bear falls on an anthill and starts getting eaten alive, demorphing while screaming. And who could forget the ant that somehow gains the morphing ability and morphs into a human only to scream in agony at gaining individuality until it dies?? FUN TIMES with the Animorphs… but also, these were stories that, rather than talk down to their audience, actually explored the grisly consequences of this great and terrible power.

It’s a classic case of judging the book by its cover; only those who actually looked beyond the cheesy illustrations were privy to the gruesome passages within. I couldn’t say if this was an intentional marketing move on Scholastic’s part, but the alternative would certainly not have helped get as many books in hands: Give the books more fucked-up/grimdark covers, and you would have either gotten a more niche subset of youngsters interested in picking them up, or have alerted parents to more closely police what their kids were reading.

It was the perfect combination: Draw readers in with childlike wonder and intrigue, then reward their intelligence with more adult stories.

ReBoot: All Fun and Games til Somebody Loses an Eye

“I come from the Net,” Guardian Bob intones in the opening credits for ReBoot season 1, which first aired in 1994, “through systems, peoples, and cities, to this place… Mainframe. My format: Guardian. To mend and defend. To defend my newfound friends.” (That’s local small business owner Dot Matrix and her annoying but endearing little brother Enzo, who has a penchant for jumping on his role model and spouting such groan-worthy catchphrases as “alphanumeric!”) “Their hopes and dreams. To defend them from their enemies.” (Viruses Megabyte and Hexadecimal, who keep trying to open portals to the Net to infect it, only to be foiled every week. What wacky fun!)

ReBoot’s premise is that inside your ’90s-era computer are dozens of systems that operate like cities, populated by sprites and binomes just trying to get by through system updates and the User (that’s you) dropping down game cubes for them to play. Nearly episode revolves around the User introducing a new game into Mainframe, forcing whoever gets caught up within the cube to play out the game as NPCs, rebooting into new costumes and personas, whether the scenario in question is a riff on Mad Max or Evil Dead. And if they lose? Oh, they just get transformed into melty little slugs called nulls, and that entire sector of Mainframe basically gets nuked.

The series never pretended at coolness, instead opting to cram in as many puns, jokes, and pop culture references as they could into that pixilated space: Mainframe’s main drag is called Baudway; there’s a walking, talking (Mike the) TV spouting infomercials; season 1’s memorable “Talent Night” episode features both a “take my wife, please” joke in binary and a three-minute guitar duel between Bob and Megabyte just because.

But by the end of season 2 and start of season 3, the show grows the fuck up, both figuratively and literally. What was previously an episodic Saturday morning cartoon becomes a grimdark serialized drama. To wit:

- The wild, untamed Web rips a portal into Mainframe, forcing Bob to team up with Megabyte to close it.

- Instead, Megabyte betrays Bob and throws him into the Web, staging a coup to take over Mainframe.

- Dot becomes the resistance leader, while Enzo takes on the role of Guardian and fumbles his way through winning the games.

- Slowly, they regain some control and build hope that they will overcome their virus overlords.

And then the User wins.

Enzo enters a brutal fighting game that is simply impossible; he does his best, and he still loses. This 10-year-old boy, right as he is starting to believe in himself, gets his eye ripped out, then is forced to become a part of the game rather than get nullified. Except that as the game cube departs Mainframe and craters the neighborhood in which it stood, that’s all that Dot sees: the destruction, and no bodies. She is convinced that her little brother is dead.

And as season 3 goes on, he might as well be: As Enzo and his best friend AndrAIa game-hop from system to system, trying to hopscotch their way back to Mainframe, they grow up at an astonishing rate, something like a year for every month—so that a year later, Enzo is a hulking, bitter mercenary in his mid-twenties who goes by the name of Matrix. His every action is an overreaction: At best he’s surly, at worst he’s trigger-happy to the point where he pulls his Gun on nearly every character in the series. He doesn’t know how to have a drink, or a conversation, without threatening bodily harm. For the season 3 arc where he narrates the intros, he identifies himself not as a Guardian but as a renegade—part refugee, part defector.

His behavior and baggage are all so extreme as to veer into the laughable, but they’re also all signs of post-traumatic stress. Enzo lost his eye because of his inexperience, so Matrix replaces it with a cybernetic eye linked to Gun, so that he will never make that mistake again. He strips himself of his Guardian credentials before anyone else can, yet if you look closely at his outfit, you can see that he keeps his arm bracers, looping them to his bulging muscles rather than discard them. He possesses a nearly pathological hatred of being identified as Enzo that belies his terror of his former self: “Number 7,” a riff on The Prisoner, puts Matrix on trial in his own subconscious as Little Enzo confronts him with a list of his failures. The renegade cannot shoot his way through his greatest fear that the ones he loves, who he’s fighting to return to, will never forgive him for what he did to survive.

On the one hand, everything about this character is turned up to 11. On the other, anything less would not have hammered home the irreversible effects of war.

You Can’t Go Back

When author K.A. Applegate wrapped up Animorphs in 2001, with one of the Animorphs dead and the PTSD-ridden survivors facing their own possibly violent end, readers struggled to understand why, some even lashing out at the series’ conclusion. Applegate responded to their negative pushback with this letter that, even if you never read the series, still tells you everything you need to know about how badass she is:

I’m just a writer, and my main goal was always to entertain. But I’ve never let Animorphs turn into just another painless video game version of war, and I wasn’t going to do it at the end. I’ve spent 60 books telling a strange, fanciful war story, sometimes very seriously, sometimes more tongue-in-cheek. I’ve written a lot of action and a lot of humor and a lot of sheer nonsense. But I have also, again and again, challenged readers to think about what they were reading. To think about the right and wrong, not just the who-beat-who. And to tell you the truth I’m a little shocked that so many readers seemed to believe I’d wrap it all up with a lot of high-fiving and backslapping. Wars very often end, sad to say, just as ours did: with a nearly seamless transition to another war.

So, you don’t like the way our little fictional war came out? You don’t like Rachel dead and Tobias shattered and Jake guilt-ridden? You don’t like that one war simply led to another? Fine. Pretty soon you’ll all be of voting age, and of draft age. So when someone proposes a war, remember that even the most necessary wars, even the rare wars where the lines of good and evil are clear and clean, end with a lot of people dead, a lot of people crippled, and a lot of orphans, widows and grieving parents.

If you’re mad at me because that’s what you have to take away from Animorphs, too bad. I couldn’t have written it any other way and remained true to the respect I have always felt for Animorphs readers.

Perhaps not coincidentally, the same year saw ReBoot’s fourth and final season nearly seamlessly transition to another war of its own. Though not before both Matrix and Bob are confronted with nightmarish younger versions of themselves: When Mainframe reboots itself, a backup copy of little Enzo is created; later, a season 2-era Bob emerges from the Web, claiming that he found a way to survive without becoming mutated like the real Bob. Despite being copies, these more “whole” versions are more readily welcomed back into society, leaving both veterans feeling like strangers in their home. Oh, and then Dot nearly marries the younger Bob, before he is revealed to be Megabyte in disguise.

Season 4 veered awfully soapy more than once, in ways that made even diehard fans like myself cringe. But again, behind that cheesiness was an examination of the characters’ real traumas. Bob has had to constantly adapt to impossible situations, has more than once given pieces of himself away in order to save his friends… and then he gets rejected. Matrix does the unforgivable to survive and grow beyond his weaker self, only for a backup to reassert itself as the “real” Enzo. Even Dot’s bonkers plot makes emotional sense: Here is someone who spent a year believing that both her younger brother and her could-have-been love were dead, who had to harden herself against the hope that they had somehow made their ways back. Of course she would cling to familiar figures, to the security of a time before the Web World Wars, before Megabyte revealed his true intentions. But the lesson here—the same thing that the surviving Animorphs carry with them—is that yearning for those former selves will only impede the healing process.

Subtlety was neither series’ strong suit, but it’s not a particularly subtle lesson. Both Jake Berenson and Enzo Matrix lose their childhoods to heroism, initially playing at some archetypal mature protector role and then actually stepping into it in the absence of any capable adults. Neither is punished, per se, for his initial naïveté, but nor is he granted the opportunity to reverse the trajectory of his life. With the power granted by a morphing cube or a Guardian icon comes responsibility, comes a clear-eyed acceptance of the consequences of playing—and then not playing—hero.

That sensibility, that respect, was extended to Animorphs and ReBoot’s viewers. Neither series is a cautionary tale; on the contrary, both establish the message that it is good and important to take on heroic roles, to emulate these beloved characters. But both K.A. Applegate and the creators of ReBoot (Gavin Blair, Ian Pearson, et al) would have been remiss if they had not emphasized the sacrifices and life shifts that come with war. Both series about transformations magical—the wonder of morphing into animals, the thrill of rebooting into new game characters—and mundane inspired their respective audiences to step up just as bravely in the real world, but also to accept that it means leaving behind a former self. What brilliance to dramatically alter their own tones, their stories and stakes, in order to teach this lesson.

When Natalie Zutter went to college, her mother made her choose between getting rid of her Young Jedi Knights and Animorphs books. She chose the latter (c’mon, she wasn’t going to buy them again) and thankfully married someone with his own YJK collection. She looks forward to her one future opportunity to introduce Animorphs to someone (i.e., her future children) without cringing. Share your favorite cheesy-but-traumatic ’90s nostalgia with her on Twitter!